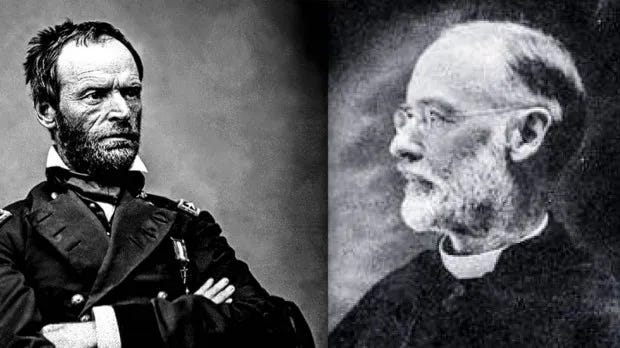

On this date, April 29, in 1933, the Jesuit priest Father Thomas Ewing Sherman died. The son of General William Tecumseh Sherman he was buried in the cemetery of the Jesuit novitiate at Grand Coteau, Louisiana.

By coincidence his grave is next to that of Father John Salter, the grandnephew of Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy.

Thomas, the fourth of eight children born of the general’s marriage with Ellen Boyle Ewing, was born in 1856.

In 1959, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy published General Sherman’s Son, written by Joseph Durkin. From the jacket:

“In 1865, as a child of nine, he stood with his mother on the White House reviewing stand while his father was honored as one of America’s greatest heroes; at twenty, he graduated from Yale and went on to study law. A year later he announced to his stunned father and overjoyed mother that he would enter the Jesuit novitiate.”

The rest is history—a rich history. Thomas was a lawyer, priest, and popular orator. In a single 200-day period he delivered 300 speeches.

He achieved much but also suffered great emotional trauma in his life.

In the Preface, John LaFarge, SJ, writes “The story of Thomas Ewing Sherman is part of our county’s history - or a sequel to a crucial phase of that history, to which today we pay an ever-increasing attention.”

One fascinating anecdote relates to General Sherman’s well-known 1864 march to the sea through Georgia—it reflects poorly on President Theodore Roosevelt and belongs in the category titled “Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?”

The unforeseen trouble began in 1906, on the day the General’s statue in Washington was unveiled. A dinner followed that evening a dinner honoring the Shermans. According to Durkin, someone mentioned that a number of West Point cadets were scheduled, for purposes of instruction, to ride and retrace on horseback the route of General Sherman’s march to the sea. Roosevelt, in what Durkin calls “a brief lapse of his sense of history and Southern psychology” invited Father Tom to accompany the officers on the trip. In the spring of 1906, the priest was on the road with the cavalry.

“The reaction of the South was immediate, sharp, and hot,” writes Durkin—but the objection was surprising. It wasn’t the ride that bothered them, nor the fact that Father Sherman was in Georgia. What upset them most was the appearance that Father Sherman felt he needed a military escort! “It was not the South’s historical memories, but its sense of hospitality that was being outraged.”

Roosevelt then made things worse. Without any communication with Father Sherman, he withdrew the cavalry when they reached Cartersville. Father Sherman was insulted, abandoned the trip, and returned to his home in Chattanooga. “Whatever his chagrin and embarrassment,” writes Durkin, “Tom Sherman was soon able to recall the incident without undue disturbance of his equanimity.”

There is much more to Tom Sherman’s fascinating life, and it’s all recorded by Durkin, including the health problems that led to his withdrawal from the Jesuits, though he did renew his vows prior to his death. It’s a great read and though it’s out of print your library may have it, used book websites—or if you’re lucky, a brick and mortar independent bookstore.

I never knew General Sherman was Catholic. Why was his son such a fan of his father’s Total War barbarism?

That’s an honest question, btw, possibly steeped in a lack of knowledge about the War. I’ve just long assumed that Sherman was a bastard, but all I know about him is that scorched march.