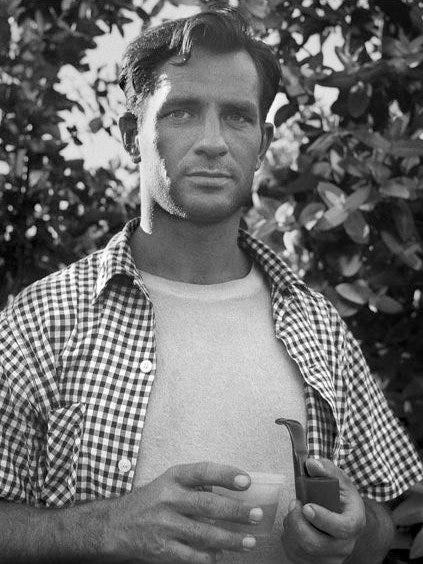

Today is the 102nd anniversary of the birth of Jack Kerouac, Catholic novelist and poet. My essay below, Kerouac and What Might Have Been, was originally published by “Dappled Things” in 2022 and can be found here.

Kerouac and What Might Have Been

Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac was 47 when he died in 1969; his death certificate listing the cause as gastrointestinal hemorrhage due to bleeding gastric varix from cirrhosis of liver, the result of "many years of excessive ethanol intake.”

To the world he was Jack Kerouac, the famed novelist of the beat generation and author of On the Road. To his mother, Gabriella, he was her “Ti-Jean,” and to his only child, Jan Kerouac - well, she knew him not, having met him twice – the second visit when she was fifteen and two years before his death when, as she told biographer Gerald Nicosia, “He was drunk, sitting in front of the TV, in a rocking chair, watching The Beverly Hillbillies and drinking from a quart of whiskey.”

Jack Kerouac drank himself to an early death; he couldn’t get off the sauce though he knew he had a problem. On March 22, 1948, ten days after his twenty-sixth birthday, he wrote in his journal:

Wrote a little – the City Episode (a reference to his first published novel The Town and the City) has been busted down at last and hogtied for fair. Its climaxes aren’t bad at all. Some people will like it better than the rest of the book, even. I also decided not to get drunk anymore, at least not the way I usually do. It’s funny I never thought of this before. I started drinking at eighteen but that’s after eight years of occasional boozing. I can’t physically take it anymore, nor mentally. It was at the age of eighteen, too, when melancholy and indecision first came over me – that’s a fair connection there. Hangovers knock me off what I could call my character-stride. It’s the easiest thing in the world for me to fall apart mentally and spiritually when drunk. Thus, no more – it’ll take time to stick to it though, but I shall do so. I seem to have a poor constitution for drinking – and a poorer one for idiocy and incoherence.

His admission, sincere yet hesitant, is reminiscent of Augustine’s fourth-century cry to the Lord in Confessions, “Give me chastity and continence, but not yet.”

Unlike Augustine, Kerouac’s “not yet” never came. What happened in the years between his journal entry and his death is an open book. His alcohol and drug use and increasingly bizarre behavior seeking sex, security and recognition is well documented in biographies, recorded memories of those who knew him, and in his own journal and autobiographical novels.

An option available to Kerouac had he been serious about his drinking was Alcoholics Anonymous. He was likely aware of the program: at the time of Kerouac’s journal entry the twelve-step recovery program was a decade old and grown nationally thanks in part to a notable 1941 Saturday Evening Post article titled, “Alcoholics Anonymous: Freed Slaves of Drink, Now They Free Others,” written by Jack Alexander.

But Kerouac never wandered into a meeting of A.A. And he probably never picked up any of its literature; had he, he may have recognized himself as if in a mirror. Was it pride that kept him away?

In As Bill Sees It, the musings of Bill Wilson, co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, Wilson delivers an Augustinian-like admonishment of pride:

“Pride is the basic breeder of most human difficulties, the chief block to true progress. Pride lures us into demands upon ourselves or upon others which cannot be met without perverting or misusing our God-given instincts. When the satisfaction of our instincts for sex, security, and a place in society becomes the primary object of our lives, then pride steps in to justify our excesses.”

Over the years Kerouac’s excesses led to his increasing dependency on drugs and alcohol and with it, great suffering – a theme woven into his books and the fabric of his life, from the deaths of his nine-year-old brother Gerard in 1926 and later his father, to his failed marriages and strained friendships, to his mother’s stroke in 1966.

Amid his suffering, drinking, and drugging Kerouac never stopped seeking serenity and peace through a curious mix of Catholicism with a sprinkling of Buddhist inspiration. Wilson connects the two, suffering and spirituality, in defining Alcoholics Anonymous: “A.A. is no success story in the ordinary sense of the word. It is the story of suffering transmuted, under grace, into spiritual progress.”

Kerouac, perhaps in debt to his Catholic upbringing, had a mature grasp of grace. In a 1949 journal entry he wrote:

Funny, too, how unsufferingly I can write now. This is perhaps the greatest Grace that has fallen on my head lately. Sometimes I’m mystified by this good fortune. God is good to me – He need not be. I am not the Lamb – not the Lamb.

Here a humble Jack Kerouac surfaces, ripe for A.A. Again Bill Wilson: “I see ‘humility for today’ as a safe and secure stance midway between violent emotional extremes. It is a quiet place where I can keep enough perspective and enough balance to take my next small step up the clearly marked road that points toward eternal values.”

Suffering, spirituality, humility, grace, perspective, balance. All this makes one wonder: what if Kerouac had wandered into an A.A. meeting while on the road? He may have found a more clearly marked road, one leading him to watch The Beverly Hillbillies sober with his daughter, peaceful and serene, healthy at age 47.

Next month I’ll be able to share a new essay on Kerouac’s 1968 appearance on William F. Buckley’s “Firing Line.” The episode has been called one of the most bizarre panel discussions ever held on television.

How sad!