General William Tecumseh Sherman’s son, Thomas Ewing Sherman, the fourth of eight children born of the marriage with Ellen Boyle Ewing, was a Jesuit priest. Born in 1856, Thomas died in 1933.

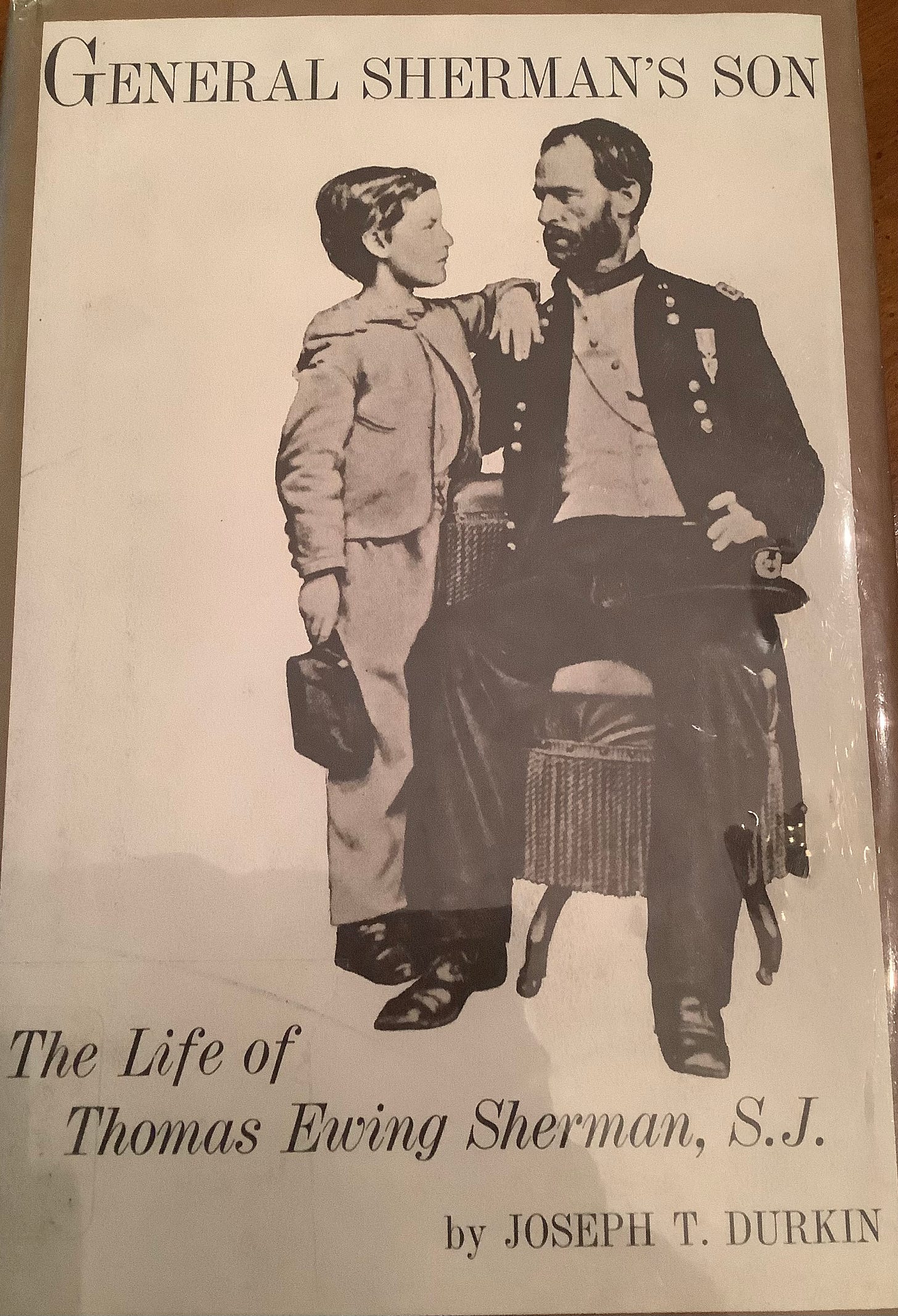

In 1959, Farrar, Straus and Cudahy published Joseph Durkin’s biography, General Sherman’s Son. From the jacket: “In 1865, as a child of nine, he stood with his mother on the White House reviewing stand while his father was honored as one of America’s greatest heroes; at twenty, he graduated from Yale, and went on to study law. A year later he announced to his stunned father and overjoyed mother that he would enter the Jesuit novitiate.”

The rest is, as they say, history. And what a rich history it is. Thomas was a lawyer as well as a priest and a popular orator. In a single 200-day period he delivered 300 speeches. He achieved much, but also suffered great emotional trauma in his life. John LaFarge, SJ, in the Preface, writes “The story of Thomas Ewing Sherman is part of our county’s history - or a sequel to a crucial phase of that history, to which today we pay an ever-increasing attention.”

Father Thomas Sherman marched to a different drummer than his father but one fascinating anecdote, among many, in the book relates to General Sherman’s well-known 1864 march to the sea through Georgia - and it reflects poorly on President Theodore Roosevelt and belongs under the category “Who Thought This Was a Good Idea?”

The trouble began, though unforeseen, the day the General’s statue in Washington was unveiled. That evening a dinner followed, honoring the Shermans. According to Durkin, someone mentioned that a number of West Point cadets were scheduled, for purposes of instruction, to ride and retrace on horseback the route of General Sherman’s march to the sea. Roosevelt, in what Durkin calls “a brief lapse of his sense of history and Southern psychology” invited Father Tom to accompany the officers on the trip. In the spring of 1906, he was on the road with the cavalry.

“The reaction of the South was immediate, sharp, and hot,” writes Durkin - but the objection was surprising. It wasn’t the ride that bothered them, nor the fact that Father Sherman was in Georgia. What upset them most was the appearance that Father Sherman felt he needed a military escort! “It was not the South’s historical memories, but its sense of hospitality that was being outraged.”

Roosevelt then made things worse. Without any communication with Father Sherman, he withdrew the cavalry when they reached Cartersville. Father Sherman was insulted, abandoned the trip, and returned to his home in Chattanooga. “Whatever his chagrin and embarrassment,” writes Durkin, “Tom Sherman was soon able to recall the incident without undue disturbance of his equanimity.”

There is so much to Tom Sherman’s fascinating life, and it’s all recorded by Durkin, including the health problems that led to Father Tom’s withdrawal from the Jesuits, though he did renew his vows prior to his death. It’s a great read and you can find copies on used book websites.