Vulgarity in literature. That’s the title of an entertaining essay written by philosopher Aldous Huxley (1894-1963). According to Huxley, in the early nineteenth century, it was vulgar to mention the word “handkerchief”’ on the French stage.

The abolition of handkerchiefs aside, Huxley’s essay often emphasizing art as philosophy is informative in many ways, including references to Charles Dickens, Dostoyevsky, and especially Gustave Flaubert (1821-1880), the French-born Catholic novelist.

Huxley found vulgarity in the works of Charles Dickens: “It is vulgar, in literature, to make a display of emotions which you do not naturally have but think you ought to have because all the best people do have them. It is also vulgar (and this is the more common case) to have emotions, but to express them so badly, with so many protestings that you seem to have no natural feelings, but to be merely fabricating emotions by a process of literary forgery.”

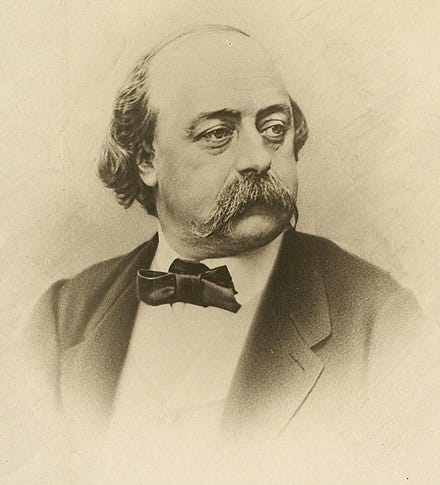

While he chastised Dickens, he admired Dostoyevsky and Flaubert. Of Flaubert’s approach to composition, Huxley opined,

“It was Flaubert who described how he was tempted, as he wrote, by swarms of gaudy images and how, like a new Saint Antony, he squashed them ruthlessly, like lice, against the bare walls of his study. He resolved that his work should be adorned only with its own intrinsic beauty and with no extraneous jewels, however lovely in themselves. The saintliness of this ascetic of letters was duly rewarded: there is nothing in all Flaubert’s writing that remotely resembles a vulgarity. Those who follow his religion must pray for the strength to imitate their saint.”

Echoing Huxley, Benjamin Ivry wrote in America magazine (April, 2022) that “Flaubert saw his Catholicism as a singular form of asceticism, allied to his vocation as a writer. Full-time devotion to his craft was a calling.”

This helps explain why many have called Gustave Flaubert the architect of the modern novel.

Gustave Flaubert, Circa 1865