John Conoley, soldier, playwright, priest, victim of the Klan

It’s a sad tale, but one that needs told. It’s the story of John Conoley - in brief.

(NB: Thanks to Dawn Eden Goldstein for pointing me to Father Conoley.)

John Conoley was born in Jacksonville, Florida in 1884. He was educated at the University of Florida, Cullman College in Alabama, North American College in Rome, and St. Mary’s, Baltimore. He was ordained a priest in 1915. In 1916, at 28, he was appointed chancellor of the Diocese of St. Augustine, Florida and secretary to the bishop.

When the Great War broke out, he asked to serve his country and in 1918 was commissioned as a US Army chaplain. He served with the 73rd Infantry and the 36th Infantry at Camp Devens, Massachusetts. In 1919 he was promoted to Captain and discharged later the same year. In 1920 he was appointed Major, Officers Reserve Corps. The same year he became rector of St. Patrick’s Church in Gainesville and Chaplain to Catholic students - of which there were ten - at the University of Florida.

Conoley was welcomed with open arms at the college. The popular campus priest also assumed leadership of the college drama club, The Masqueraders - a natural interest of Father Conoley who had already written a number of plays.

He was also popular off-campus, in his parish, and was widely engaged in the community. He was a charter member of Kiwanis, and a member of the American Legion and the Military Order of Foreign Wars. A gifted orator, he was often invited to speak throughout the region, speaking at length on civic ideals. The Ocala Evening Star reported on one such talk given to the local Rotary Club:

Rev. John Conoley made the principal address of the evening. He called attention to the fact that a city is what its individuals are. He pointed to the wide-spread breakdown in the family life of the nation and made a plea for a return to the sanctity of the nation's hearthstone.

He pointed to the very general chafing under restraint. He charged that the licenses of the hour are being fostered by the cheap magazines and the movies. “You men can make your city what you will,” said Rev. Conoley.1

Another talk, delivered to the American Legion, was covered by The Tampa Tribune:

“We must, labor with might and main to secure ‘America for Americans,’ native born or naturalized, whose devotion to the ideals and traditions and institutions of our country is so obvious, so genuine as to be beyond doubt,” said Father Conoley in his address.

Conoley’s popularity grew dramatically both on and off-campus through 1923, and the number of Catholic students at the secular college increased four-fold.

And then, in February of 1924, he suddenly disappeared - the victim of a kidnapping and brutal beating orchestrated by the Ku Klux Klan.

The hatred of the Klan for the Catholic Church in the early 1920s Florida is well-documented but, as Stephen Prescott wrote in the Florida Historical Quarterly (Vol. 71, 1992), “John Conoley was an unlikely protagonist in this tragic drama.”

What triggered the kidnapping? A speech and an editorial.

It was a simple speech (perhaps perceived as “the final straw” by the Klan who apparently had been following Conoley’s growing popularity for years) delivered in the fall of 1923 to the Kiwanis Club of Gainesville. The speech was followed the next day by a glowing front-page editorial by the Gainesville Daily Sun. The essence of the speech seemed fairly innocuous: a plea for local businessmen to hire university students. The paper described Conoley as a “fluent and gripping speaker,” praised his speech, and claimed the priest “said more in those eleven minutes than we have ever heard in the same length of time.”2

This praise for a Catholic priest by the local paper aroused the local Klansmen who were pursuing a hate campaign against any elements that they considered disloyal and anti-American. The Klan perceived Catholics as being under the control of the church and loyal only to the pope. At night during the last week of September 1923, the Klan distributed leaflets on the doorsteps of homes in several Gainesville neighborhoods and left multiple copies at the local restaurants. The flier referred to Conoley’s speech and the Gainesville Daily Sun editorial. It attacked Conoley’s motives and accused him of attempting to subvert the faith of Protestant students and to convert them to Roman Catholicism3

The leaflets triggered a groundswell of calls on the university president and trustees for the removal of Father Conoley, but they vigorously defended him. However, over time, as pressure grew, official support wilted. He was first removed as advisor to The Masqueraders, and soon after, banned altogether from campus - all to appease the bitter complainers.

But the Klan was not appeased: “…three hooded Klansmen entered the rectory of St. Patrick’s on a February weekend in 1924. (Gainesville) Mayor George Seldon Waldo and Police Chief Lewis Washington Fennell were allegedly two members of the trio; the third Klansman was never publicly identified.”4

The Klansmen left Father Conoley severely beaten on the steps of the Catholic church in Palatka, forty miles from Gainesville. The Good Samaritans who discovered him took him to a Gainesville house that provided nursing services (Gainesville had no hospital at the time).

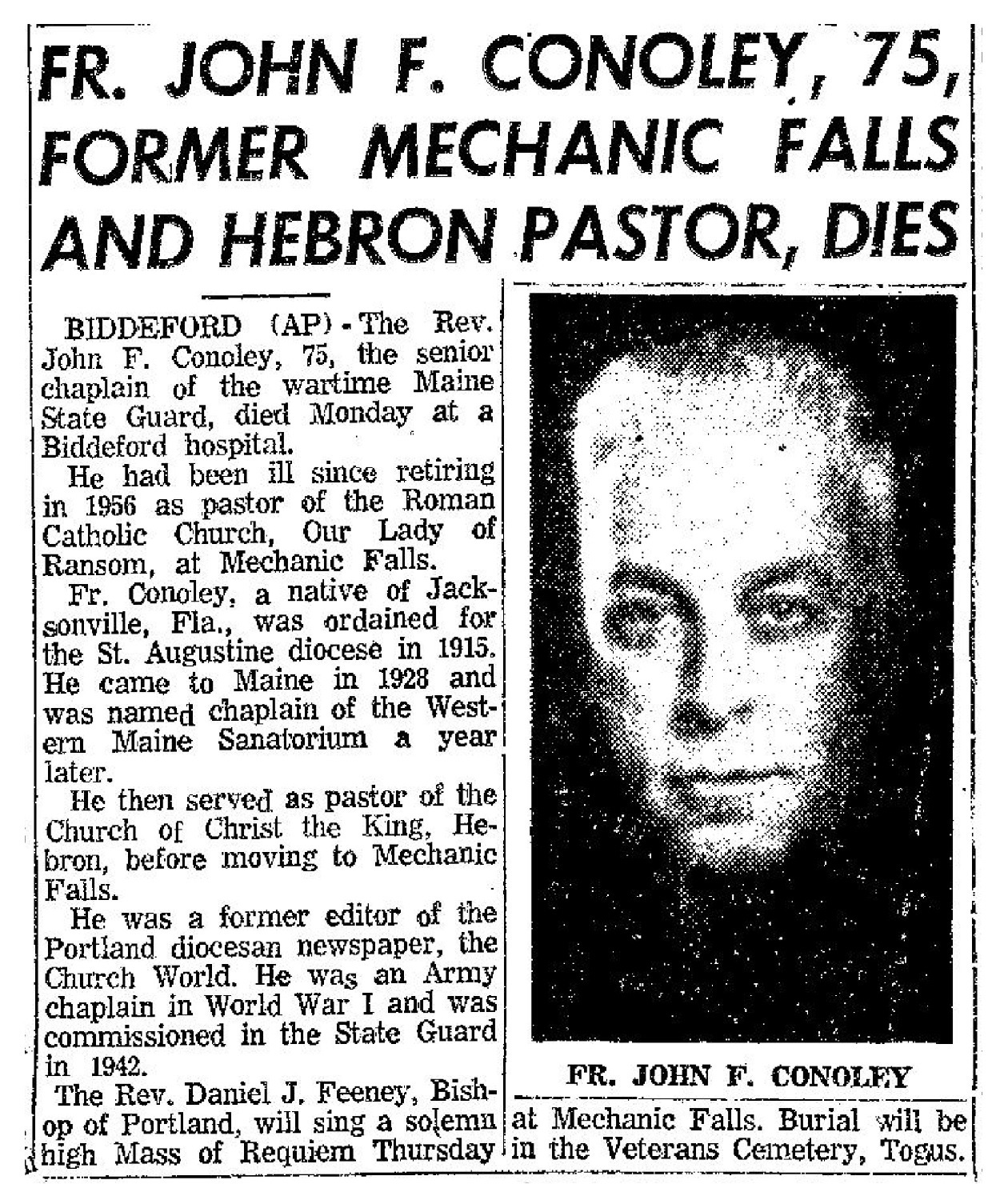

After his convalescence in the Gainesville nursing home, Father Conoley was sent to Washington where he was hospitalized for a year. Apparently, he was both mentally and physically ill. He then spent two years in a monastery and afterwards was accepted as a priest in the diocese of Portland, Maine. Conoley served as a diocesan priest there until his retirement on August 31, 1956. Father Conoley died July 25, 1960, and was buried at the Veterans Cemetery in Togus, Maine.5

According to the item in the Florida Historical Quarterly, no arrests were made. Obviously, at the time, the Klan had the support of those in the highest levels of local government. There was no known public response to the attack on Father Conoley. The local paper did not report it, nor was there a police investigation. Many people, including students at the university, must have wondered about his disappearance. He was too public a figure in Gainesville and on the campus for his sudden departure to have gone unnoticed. The official record does not record any protests, questions, or explanations. Father Conoley was gone. It was as though he had never had a life in Gainesville. Three priests were assigned over the next four years to assume his duties at St. Patrick’s and at the university.

Gradually, both in town and at the university, the number of Catholics increased. One of Father Conoley’s successors, Father Jeremiah P. O’Mahoney, who arrived in 1928, was a much beloved figure on campus and in the town. In later years he received an honorary degree from the University of Florida.6

The lack of accountability for the attack on Father Conoley coupled with the acceptance and success of the priests who followed in his footsteps adds to the mystery of his targeting by the Klan.

Father Conoley lived another forty-five years, most of those far north in Maine. I could find no evidence he ever returned to Florida, or spoke publicly of his ordeal.

May he rest in peace.

The Ocala Evening Star, July 28, 1920. https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-ocala-evening-star-conoley-rotary-ad/146581466/.

Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 71, No. 1, 1992.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.